From Intention to Action:

We Speak to Perform

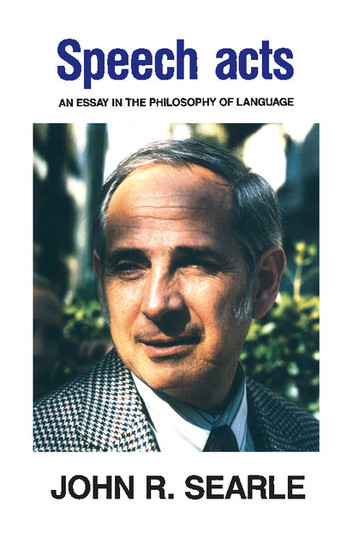

Hello everyone! I am a Computer Science major undergraduate who happens to encounter Linguistics during my studies. As a science student, it would be very natural for me to think that a sentence is either true or false, like the utterance “ten is larger than one hundred” is clearly wrong. That kind of truth-value is useful for science research, but Dr. John Searle offers a different perspective of how we see and use language in his book “Speech Acts”.

Searle has adopted the term “Speech Acts”, indicating that sentences do not merely describe the world around us, they are actions we perform with a particular intention. When I plead with my professor, saying “Please don’t fail my course,” under this context, whether the sentence is true or false is no longer important. What truly matters are the conditions we have to meet when I make the request. These kinds of assumptions are exactly what Searle would like to discuss. When I beg my professor, I know that he is in a position to save my grade, so I should approach him with a sincere and pitiful tone and make sure he feels that way. If he understands my intention, then Searle would say that I have successfully performed the act of begging. Searle argues that all speech acts can be seen as performatives, meaning that every utterance is an action in itself.

Linguists might analyze a sentence’s meaning literally, word by word, that is to say we can calculate its meaning by the definition of every word in it, and how these the meanings of these words can be combined into the meaning of the sentence. However, Searle opposed this theory, proposing that the meaning of the utterance is simply the speaker’s intention. Consider an old man who can barely speak, if there is a cup of water and a muddy liquid on the table, and he says “give… mmm… ahh… drink…”. Just by looking at the sentence itself, we might not decipher his words literally, but I believe normal people would understand what he is trying to say and his desire for water.

From other perspectives, can we perform the act of promising without using the word promise? How is it possible to perform a deceptive promise? And if we discover that Confucius was from Japan, can we still identify him as the Chinese philosopher we know? If you are interested in getting insights and enlightenment to these questions, I recommend reading this classic in linguistic philosophy by John Searle, which allows you to rethink what language is, and how we can formalize language use through novel definitions.

.png)