Renditions

No. 51 (Spring 1999)

By Linqing

Translated by Yang Tsung-han and John Minford

Upon leaving the Fairy Hermitage and its delights, I lifted my head and saw that the setting sun was approaching the hills. Adjusting my dress, I was about to go on my way, when Wang Pushan asked me if I had ever visited Sui Garden.

"No," I replied. Wang pointed to the east, to a pagoda, and said:

"That is Mount Xiaocang, and at its foot lies the garden first owned and constructed by a Director of the Imperial Silk Textile Workshop named Sui. In the days of Qianlong, the Academician Yuan expanded the garden when it came into his possession, and changed its name to another Sui, written differently and meaning something different.

"At various times he wrote six short essays in praise of his garden. Let me quote his own words:

My garden is both deep and spacious. Pass from one room to another: each one is enhanced with the shining radiance of mirrors, so luminous and bright, that when walking through them one loses one's way. It is a place suitable for both walking and sitting. A high tower stands as 'screen' to the west. A clear stream flows eddying through it, ten thousand bamboos form a sea of verdure. You need never fear the oppressive heat of summer, neither heat-wave nor heat-stroke; and in winter since the windows are fitted with transparent glass, you may see the snow and not feel the wind. There are one hundred plum trees, more than ten groves of cassia trees. The trees cast clear shadows when the moon rises, their fragrance wafts on a gentle breeze. This is a place for the pleasures of spring and autumn alike. With continuous corridors and walkways to stroll in, one need not abandon one's pleasure in walking even during rain, lightning, thunder or gale—it is a place suited even to stormy weather.

"The Academician has passed away; the garden is deserted. And yet the charm of the place is unchanged! Why don't you go there and take a look?" concluded Wang.

|

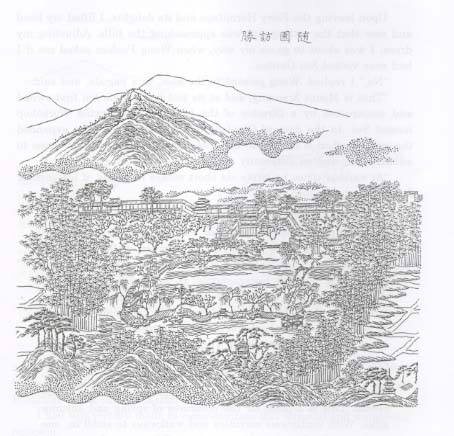

"I most certainly will!" said I. I found the path and had soon reached the garden. I saw that it backed onto the hill, which formed its rear wall. Buildings stood beside the stream, and a pavilion was hidden in the depths of a valley, while a bridge led to a short embankment. There was nothing grand or imposing about it, but it had a subtle charm and intricacy of its own, very like the delightful literary style of its most recent owner, the Academician Yuan of Xiaocang Mountain Studio.

This Academician was named Yuan Mei, and hailed from Qiantang in Zhejiang province. In the year jiwei of the Qianlong reign (1739) he passed his jinshi examination under my great-great-grand-uncle Sire Songyi, of whom this same Academician once wrote a biographical study, in which he expressed his profound gratitude to the kind favour of the senior scholar, who had been both his principal examiner and also on another occasion his sponsor. This biographical essay was included in Yuan Mei's Complete Works from the Xiaocang Mountain Studio. I only regret that I was born too late to have had the privilege of paying homage to him in his garden.

Among the successful jinshi candidates of that year under my ancestor, those that went on to serve in lucrative official posts, or to enjoy great literary fame, were too many to be counted on one's fingers. However, with Yuan Mei, there were Shen Guiyu, Board President, and Qi Cifeng, Board Vice-President. Together they were known as the Three Legs of the Tripod.

Back to table of contents

Research Centre for Translation, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.